One serious problem with the available books on English grammar is that there are so many written by unqualified people. Take this one for instance: A grammar book for you and I…oops me!. The author is a lawyer. He has no special education related to grammar or language analysis. What makes him think he can write a book on the subject? And more to the point, why do people buy things like this? Could I write a book on law and get taken seriously? I should hope not. Why on earth would anyone expect a lawyer to know anything about grammar analysis?

I mean just look at what the first chapter is called: “the eight parts of speech”. This a bad start. When the author says 8, he really means just 8.

every time you reach in, grab a word, and use it in a particular sentence the word comes from just one of these eight compartments.

…

Amazing, huh? You can compartmentalize the entire English language into just eight categories.

It’s not amazing. It’s wrong. English words don’t have inherent or fixed parts of speech. And eight parts is not enough to capture all of English. And interjections are damn near useless as a category. This post explains everything.

When you reach into your bag of words and plunk them down on paper, you organize them into chunks. This group of words does this thing, that group of words does that thing. Rarely do you pull out just one word and end the writing project right there

This is true, and a point worth making, although I’d like to clarify that this chunking happens in your brain first, and on paper second. The more technical term for these chunks is “constituents“. This is a concept that is basic to syntax. If you don’t understand what a constituent is, you can’t understand what a phrase is. And speaking of phrases…

All groups of words break down into two types: phrases and clauses. The sole distinguishing features of a clause is the presence of a conjugated verb.

One thing I like about this definition is that it’s clear and simple. But despite those positive attributes, it’s still wrong.

Consider this sentence:

I am eating apples with peanut butter.

Inside that sentence is the string eating apples with peanut butter. This string forms a constituent, meaning it behaves as “one unit” for certain purposes. One way you can show this is that you can replace the entire thing with so as in:

I am eating apples with peanut butter and so is Jenny.

As an aside, that word so would be called a pro-verb. This is like a pro-noun, except that it replaces verb phrases instead of noun phrases. More generally words of this type are called “pro-forms”. (This is something not enough grammar books mention.)

Anyway, since eating apples with peanut butter has a ‘conjugated’ verb, by the author’s rules this would either not be a phrase (which is incorrect, it’s a verb phrase) or it would necessarily be a clause (which is also incorrect). I think, judging from his examples, that he would not consider it a constituent at all, and instead call all of I am eating apples a clause. Or maybe the whole thing would be a clause? He doesn’t give a definition of “sentence”, so I’m not sure if there’s any level higher than clause. It’s all a little confusing. It’s a nice looking definition, the simple language makes it more appealing, but it needs some work. This misconceptions about phrases carries on throughout the chapter on nouns.

How do you make a noun possessive? For singular nouns, just add “apostrophe s”; for plural nouns ending in -s just add an apostrophe. The rule is easy to follow but trips up a lot of people

That’s because the rule is wrong. Indeed, I see that the author himself has just been tripped up by it. Possessive is not marked on nouns – it’s marked on noun phrases. For example:

The man in the white coat

The man in the white coat’s passport.

*The man’s in the white coat passport.

The possessive goes at the end of the phrase, on coat, even though the passport doesn’t belong to the coat. It’s ungrammatical to put the possessive right on man, even though the passport belongs to the man.

And the problems go deeper than phrases. Turns out the author can’t reliably identify some specific words either. In discussing the American national anthem, he takes the time to point out something about the line by the dawn’s early light.

Notice that the word dawn’s does not really serve a traditional function as a noun. It’s really acting as an adjective. You can see this feature of our language by recognizing that dawn’s is not the object of the preposition by.

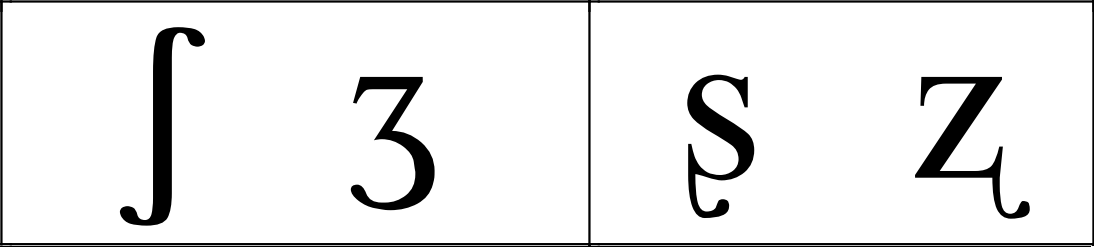

This is just so wrong. So what if it isn’t the object of the preposition? That doesn’t mean it can’t also be a noun. Let’s diagram that phrase out.

But of course, that’s only a picture. You could just as easily write “Adjective” there and prove his analysis correct. The reason that dawn sits inside a noun phrase is because it has a possessive affix on it. And that’s the part that blows my mind – this appears after a section on noun possession. Did he read his own book?

Or maybe he is above his own advice. He does seem to endorse an authoritarian approach to grammar. You should just do whatever the authorities tell you, even if it turns out they are incompetent.

And people in power- bosses, teacher, lovers – know the rules by heart. Or pretend they do. They expect you to follow the rules.

Wait a minute…the author is someone in power, or at least presents himself as an authority. So was that just a tacit admission that he is only pretending to know the rules? This is a terrible argument anyway. It’s letting the crazies win.

This book is filled with appeals to authority and unjustified arrogance. I think the peak moment is his argument that the passive voice doesn’t exist in the future progressive. The reason? Because he wants to feel smugly superior to anecdotal college professors:

Then one day I got a rather nasty letter from some English professor at a small college in a state I won’t name. He tore into me, saying ‘Oh yeah? What’s wrong with the future progressive passive will be being shown?’ I soothingly wrote back:

‘There’s nothing wrong with the construction, sir. It simply doesn’t exist, except perhaps in [name of state].’ Whew. Writing a book on grammar takes some guts.

It should take brains. I don’t see why we should consider this guy’s personal opinion to be special. He is trained to be a lawyer and has no particular qualifications to be writing a book on grammar, whereas an English prof might actually know something about passives. An ad hominem attack on an anonymous college professor is not a persuasive argument, and does nothing to support his contention that the passive is not used in the future progressive. A quick search on Google turns up thousands of results for ‘will be being shown’, so it obviously exists in many places, other than [name of state].

At the time, I couldn’t find an authority for my statement. But now I can cite Thomas Kane.

At the time? So when he replied to the college professor, it was an argument based on…gut feeling? Personal whim? A desire to always be right? Why wouldn’t he do the research part first? After all, the professor wrote to him; it wasn’t a question in a live debate. There was time to go look up a supporting source before replying.

[update: I’ve been contacted by the author of this book, and you can read his reply in the comments section below. I earlier incorrectly stated that he had cited Thomas Katen without providing a reference. In fact, the correct name was Thomas Kane, and a reference does appear. I apologize for this error.]

And who is Thomas Kane? He is listed as the author of the 1983 Oxford Guide to Writing. This is barely “citing” someone, since there are no supporting arguments from Kane reproduced for us to read, or any suggestion of why Kane’s work is relevant here. The mere reference to an authority is apparently supposed to be enough. Moreover, it is unclear that Kane is even an appropriate reference in the first place. I was unable to find a copy of the 1983 “Oxford Guide to Writing”, so I couldn’t check the original source, but I was able to look up Kane’s 1994 “New Oxford Guide to Writing” online. This not a grammar book, as the title makes clear. The main sections of the book are “The Writing Process”, “The Essay”, and “The Expository Paragraph”. There is no section specifically devoted to grammatical voice, and using the Google Books search function, I could find no discussion of the passive that is any way relevant to the claim that the future progressive passive doesn’t exist.

It’s no wonder we lament the public’s poor grasp of grammar. When people as ill-informed and pompous as this can write a book on language and get taken seriously, things really are in bad shape.

It’s been apparent to me for a while that the publishing industry is so starved for content that merely writing a book that seems even vaguely publishable is almost a guarantee of being a published author.

For grins I Googled [Thomas Katen] and found no hits of any significance. But are we surprised that lawyers make things up? We are not. Shakespeare had an interesting take on lawyers; maybe we first start with the lawyer-grammarians. :D

LikeLike

I want to be on your side about the eating apples sentence, but is this sentence supposed to be “I am eating apples…” or “I love eating apples…”? Sorry, just a little confused.

LikeLike

Oops! I had originally used the sentence “I love eating apples”, but then changed to “I am eating apples”. I guess I didn’t replace everything that I thought I had. Your turn to keep me on my grammatical toes. Thanks!

LikeLike

I admire your courage. You dared to open and read a book whose short title manages to murder the natural cadence of the spoken word with continuation marks and an exclamation mark. Double shudder.

Now, at least, I have learnt about grabbing words from a choice of eight different compartments and plunking them on paper. Chunky, but organised. I relished your responses at every turn.

I am just curious though (and please bear in mind that it is a very long time since I drew the duck-feet diagrams):

In the phrase “by the dawn’s early light”, it is not possible for “dawn’s” to be shown as subordinate to “light”, since the simplified structure without the duck feet would read, “by the early light of the dawn”?

Plunk… plunk… plunk!.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s another view of it, and I would have drawn “by the early light of dawn” differently. I should say that tree diagrams like this are mostly intended to represent sentence structure, in particular constituency. But there is another diagramming system that focuses on representing “modification”. TheBestOfAlexandra, who posted a comment above, does this kind, like here for example.

And now you have me questioning if I did other things wrong in there. Maybe I should have actually moved up the so that’s it’s daughter to the top NP (the one headed by light, not dawn). Edit: I decided to make this change.

LikeLike

I prefer the tree diagrams. If this diagram amateur were drawing, she would draw “by the light” and then fill in the other constituents. But, as Mr C. Edward Good might say, writing on blog on grammar “takes guts”.

LikeLike

You wrote: “As for citing Thomas Katen, it never actually happens. There’s no actual citation or quote or even a hint of who Thomas Katen is. He just mentions the name, hoping that we’ll be impressed by this lame appeal to authority, and leaves it at that. It’s not really even a citation – it’s a name drop.”

If you’ll read more carefully, on page 232, you’ll find the name I cited: Thomas Kane. And if you’ll Google “Thomas Kane Grammar,” you’ll find his work: The Oxford Guide to Writing. It’s fully cited at page x in my book.

Let’s see now: “lame appeal,” “name drop.”

I’ll accept your apology and your correction.

Ed Good

Author

A Grammar Book for You and I … Oops, Me!

LikeLike

Hi,

I’ve been away from this blog for quite a while and only recently noticed your reply here. Thank you for bringing this to my attention. I did indeed make a mistake with the name of your source. I don’t know where I got the name “Thomas Katen” from, or why that persisted in my notes for so long. The correct name is “Thomas Kane”, and indeed there is a reference to Kane at the end of your book. For this I really do apologize, and the error is wholly my own. I have edited out the offending part of my post.

However, this does not lend any extra credibility to your claim that there’s no such thing as a future progressive passive. Since I now have the correct citation, I went to look up Kane’s work, and I cannot see how his work supports your claim either. I have added an apology into the text, and the following paragraph has also been added.

“And who is Thomas Kane? He is listed as the author of the 1983 Oxford Guide to Writing. This is barely “citing” someone, since there are no supporting arguments from Kane reproduced for us to read. The mere reference to an authority is apparently supposed to be enough. Moreover, it is unclear that Kane is even an appropriate reference in the first place. I was unable to find a copy of the 1983 “Oxford Guide to Writing”, so I couldn’t check the original source, but I was able to look up Kane’s 1994 “New Oxford Guide to Writing” online. This *not* a grammar book, as the title makes clear. The main sections of the book are “The Writing Process”, “The Essay”, and “The Expository Paragraph”. There is no section specifically devoted to grammatical voice, and using the Google Book’s search function, I could find no discussion of the passive that is any way relevant to the claim that the future progressive passive doesn’t exist.”

LikeLike

One more thing: http://library.thinkquest.org/2947/partsofspeech.html.

LikeLike

This is a dead link. I am redirected to a page that says ThinkQuest has been down since July 1, 2013.

LikeLike

This is just too much.

Your review of the Tarzan and Jane book (link above):

“There’s one novelty: Jane actually goes through the 9 parts of speech. Usually, there are only eight.”

Your review of my book:

“I mean just look at what the first chapter is called: “the eight parts of speech”. This a bad start. When the author says 8, he really means just 8. It’s not amazing. It’s wrong. English words don’t have inherent or fixed parts of speech. And eight parts is not enough to capture all of English. And interjections are damn near useless as a category.”

So you slam the Tarzan author for the failure to say there are eight parts of speech.

And you slam me for saying … drum roll … there are eight parts of speech.

Just what is it you’re so angry about?

LikeLike

The use of 9 parts of speech is not specifically what made the Tarzan book bad. It was in fact one of the few positives things I could find about it. It’s entirely reasonable to split nouns and pronouns into different categories, based on their morphosyntactic properties. I have explained in many places on this blog that I generally reject the traditional 8 parts of speech model, and the 9 part model in the Tarzan book suffers from virtually all the same problems (e.g. the arbitrary use of semantics or syntax to justify categorization, the use of interjections, etc.)

LikeLike

You assumed too much and seem to be on a high horse, author dear. And not everyone has to follow your framework of 9 parts, you are entitled to your own opinion of course, even if it be an unpopular one. It seems the motivation for writing such a post is more jealousy than anything.

Thank you Ed for writing such an amazing book! :)

LikeLike