English is traditionally described as having “long” and “short” vowels. Despite this terminology, the distinction has nothing to do with length. In fact, a long vowel is one where the pronunciation matches the name of the letter. For example, the “a” in “made” is a long-A, because it is pronounced like the name of the letter A. The “o” in “throne” is another example of a long vowel, this time a long-O. Short vowels, on the other hand, have unpredictable pronunciations. Despite the name, they are not short versions of the long vowels. They are actually completely different vowels with no relation at all to their long counterparts. The “a” in “mad”, or the “o” in “done”, are considered short vowels because their pronunciations do not match the names of the letters.

This is a system of vowel classification that just doesn’t work. The fundamental problem is that it is based on the letters of the alphabet. Since there are only 5 vowel letters, you can describe at most 10 possible vowels. However, all English dialects have more than 10 vowel sounds, which means that the long/short classification is doomed to failure. There are always going to be some vowel sounds that cannot be represented, because there aren’t enough symbols to keep them all distinct.

For example, consider the “a” in “lack” and the “a” in “father”. Neither of them is like the name of the letter A, nor are they like the name of any other vowel letter, so they would both have to be classified as short-A. This is clearly wrong. These are distinct vowels, and it is wrong to lump them together as examples of the same category.

To add to the confusion, the “a” in “father” represents exactly the same sound as the the “o” in “lock”. Is this vowel in “lock” a short-A, because it sounds like another sound called short-A? Or is it a short-O because it spelled with an “o”? Neither option is desirable. Another example: what do we do with the vowel in “food” and the vowel in “rude”? It’s the same vowel in both cases, but spelled with different letters. Is this sound a short-O in “food” and a short-U in “rude”? Why call it a different name when its the same thing? (And why would a short-O be spelled with a doubled letter?) Speaking of “u”, the long-U sound isn’t even a vowel! The name of the letter U is a a full syllable; it is a sequence of a consonant [j] and a vowel [u].

You might wonder why the letter Y is not part of this categorization. That would allow for 2 more vowels into the sytem, for a total of 12. However, there doesn’t seem to be any long-Y sound. The letter Y never represents a sound like its name [wai]. (Except, maybe, in the word “why”.) Sometimes, Y represents a consonant, as in “yellow” or “Mayan”. Other times, it represents a vowel, and there are at least three different vowels it can be: “thyme”, “rythm” and “baby” all have different “y” sounds. You might expect these could be called short-Y sounds, but I that doesn’t seem to be very common. Instead, it seems like people refer to these as short-I sounds, which makes no sense to me at all.

A quick lesson in phonetics

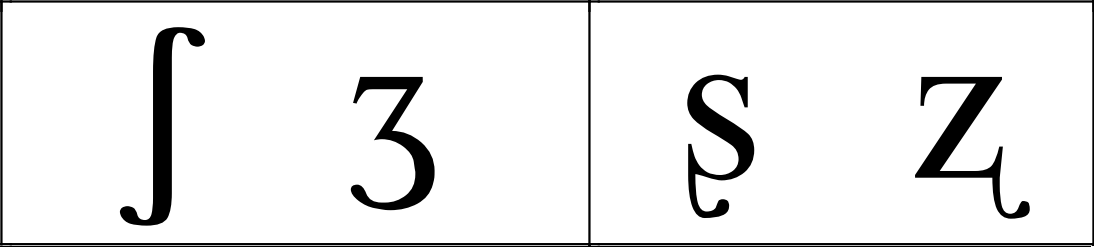

To understand the vowels of English, you can’t think of them as letters. You have to think of them as speech sounds. Sounds and letters are completely different things, and this really matters. Talking about sounds gives us the proper level of description. A quick introduction to phonetics will help clarify thing. I should make a note here: phonetic symbols are represented using square brackets, like [s]. If I need to refer to spelling letters, I’ll put them in quotes like this “s”. So the letter “s” can represent the sound [s], as in “sap” or the sound [z] as in “miser”.

To produce speech, air is pushed out of your lungs. It travels past the vocal folds in your throat, possibly causing them to vibrate and make noise. (Here’s a video the vocal folds of four singers. It’s probably the weirdest thing you’ll watch today.) Finally, the air escapes your body, either through your nose, your mouth, or both. If air is trapped or forced around constrictions during this journey from lungs to outside world, then the sound is considered a consonant. If the air flows more or less freely, then the sound is considered a vowel.

For example, to make the sound [s], your tongue tip has to raise up behind your top teeth so that air is forced through a narrow constriction (which is what gives [s] its characterisic hissing sound). Therefore, [s] is a consonant. On the other hand, the sound [a], the first sound in the word “on”, is made without any obstruction in your mouth at all. Therefore, [a] is a vowel.

What makes consonants different from each other is the location of the obstruction, and what the air has to do to get around it. If you close your lips and re-direct air through your nose, you can get an [m] sound. If you press your lower lip to your upper teeth and blow air through quickly you’ll get an [f] or [v].

Vowels don’t have any obstructions, by definition, so what makes vowels distinct from each other is the size and the dimensions of the space that air flows through. One way you can control the size of this space by moving your jaw up and down. The word “see-saw” is a good example of this. Say that a few times. For “see”, your jaw is raised, and for “saw” you lower the jaw and open your mouth wider.

What you do with your tongue also changes the dimensions of your mouth, and therefore changes the quality of the vowel that you produce. The vowel in “phone” has a higher tongue position than the vowel in “fawn”. The vowel in “boat” has the tongue further back in the mouth than the vowel in “bet”. These changes in position are actually a little tricky to feel without some practice. Linguists normally study the phonetics of vowels by using ultrasound machines (and X-rays way back in the day when people thought that was safe). There’s a really nice website where you can click on a phonetic symbol to watch an ultrasound video of someone’s tongue producing that sound (consonants here, vowels here).

In linguistics, vowels have two major characteristics: their “height” and their “backness”. These terms refer to the position of the tongue when articulating the vowels. High vowels are produced with a tongue closer to the roof of the mouth, while mid and low vowels are produced with lower tongue positions. Back vowels involve a retracted tongue, while central and front vowel have a tongue tip closer to the teeth. There are many other properties of vowels that may be relevant in a language, such as nasality (whether air flows through the nose or not) and roundedness (whether the lips are rounded or not). I won’t discuss vowel phonetics in detail here, but if you want to read more about it I have a post over here.

This is short take-away message: Classifying vowels on the basis of their phonetics ensures that we can tell all of the vowels apart. In traditional terms, the (distinct) vowels “father” and “lack” are both short-A. In phonetic terms, the vowel in “father” is a low back vowel, while the vowel in “lack” is a low front vowel. In other words, they differ in their “backness”. This is an improvement on the traditional terms which would classify them as the same vowel.

I think it would make far more sense to get rid of the traditional notions of “short” and “long” and start teaching people something useful. A phonetics-based approach teaches students about how pronuncation actually works, and it’s a model that you can use for literally any language on Earth. All humans have basically the same vocal tract anatomy, so the phonetic terms you learn for English will, more or less, work for any other language you might study later. The traditional terms “long” and “short” will be useless for other languages.

It’s not even that hard to remember terms like “high/mid/low” and “front/centre/back”, because these are terms that actually refer to something real. In contrast, the traditional terms “long” and “short” are totally arbitrary labels that students simply memorize. There is no additional insight gained into how language works. In fact the traditional terminology obfuscates things by labelling distinct phonetic vowels as the same (“lack” and “father” both have short-A).

Are “short” and “long” useless labels?

I should say that there is nothing wrong with the idea of “long” and “short” vowels, in general. In many human languages, the length of a vowel, meaning the duration in milliseconds, is something that actually matters. For example, Thai has both long and short vowels. The word [cip], with a short vowel, means “to sip” while [ci:p], with long vowel, means “to flirt” (the common phonetic notation for a long vowel is to add a colon after it). The word [het], with a short vowel, means “mushroom” while [he:t], with a long vowel, means “cause”. In one experiment, a native speaker of Thai was recorded producing pairs of words with long/short vowels, and the length of his vowels was measured. The short [i] in [cip] lasted 30-35 milliseconds. The long [i:] in [ci:p] lasted more than 100ms. That’s enough of a difference that I suspect even a non-native speaker would notice it. I should add that length isn’t everything. Long vowels and short vowels may also differ in other phonetic properties as well.

While we’re at it, it’s not just vowels that can be long. Consonants can be long too, but in this case they are often referred to as “geminate” consonants. For example, in Norwegian words can differ by consonant length: sine means “theirs” while sinne means “anger”. Note that a double “n” doesn’t mean that you say two [n] sounds in a row. Rather, you say a single [n] but the pronunciation lasts for a longer period of time.

A return to English vowels

Now here’s the interesting thing: English actually does have short and long vowels, meaning vowels with different physical durations. However, vowel length in English is quite a different phenomenon from Thai. The difference is that the length of a vowel in Thai is completely unpredictable. You can have two words that are exactly identical, except that one of them has a longer vowel (I gave some examples earlier like [het] “mushroom” and [he:t] “cause”). You cannot formulate a general rule for when a vowel will be long in Thai – you just have to memorize vowel length with every word that you learn.

In English, on the other hand, the length of a vowel is completely predictable. If a vowel comes before any of these sounds [p,t,k,f,θ,s,ʃ], then it will be short. Otherwise it will be long. In phonetic terms, vowels are short before voiceless consonants, and long before voiced consonants.

You can do a quick experiment to see this yourself (assuming you are a native speaker of English). Say “ice”. Say “eyes”. Note how the vowel in “ice” is shorter and the one in “eyes” is longer (in non-technical terms, you might say that the vowel in “eyes” is more drawn out). This is because in “ice”, which is phonetically [ais], the vowel is before a voiceless consonant. In “eyes”, phonetically [ai:z], the vowel is before a voiced sound.

Here are some other pairs to consider:

short/long

feet/feed

neat/need

greet/greed

cap/cab

price/prize

lap/lamb

To really get a sense of this, you should literally say these words out loud. Whispering or talking in your head is not the same thing. To get the right phonetic qualities, you need to say these in a normal speaking voice at a normal speaking rate. It can help to put the words in a short sentence so that you get into a natural speaking rhythm, something like “The first word is feet, the second word is feed”. (In real-life phonetics experiments, this is exactly what scientists ask participants to do.) I always tell new students that talking to yourself is considered professional behaviour in linguistics, so don’t be afraid to do it.

Does length matter?

Of course, if you wanted, you could pronounce any English vowel as long or short. It doesn’t really matter, because the distinction in English doesn’t contribute to any difference between words, unlike in Thai. If you pronounce an English vowel that’s normally long as short instead, it won’t change the meaning of the word. If you do this all the time, people may think you have an accent, but they’ll understand what you mean. On the other hand, if you swapped long and short vowels in Thai, you would say some very confusing sentences.

Let’s put this in technical terms: vowel length in Thai is “phonemic”, meaning that it distinguishes words, and in English it is “allophonic”, meaning that it never distinguishes words and is a predictable effect of pronunciation.

The concepts of “phonemic” and “allophonic” apply to all languages. Phonetic terminology too is universal. I think that these are core concepts that should be included in standard English language education. Trying to get people to learn about English with the traditional vowel-length categories is crazy, and it will never work properly. There is a real system to the way that vowels work in English, and it is possible to describe them with sophistication. I think it’s time to abandon the old system of vowel length, and bring in something based on phonetic sciences.

Hi, thank you for a great post! Although I think it’s important to notice that some dialects of English do have phonemic length (or that it’s a matter of debate). The famous ship~sheep example — most American speakers don’t distinguish them by length, but I believe that some non-rhotic dialect speakers do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for pointing that out. I should have been more careful about my wording here. I’m a speaker of Canadian English, and I’m assuming that (most) of the people reading this blog speak or are learning some variety of North American English. I should still be explicit about that assumption, and you are correct that some of what I said in the post doesn’t apply to every variety of English.

LikeLike

Yes, you really should be careful to say “North American English”, and even then there are complications. Eastern New England, for example, has the COT-CAUGHT merger but not the LOT-PALM merger you describe here.

Australian English definitely has length-based distinctions. It has no low back vowels, with the result that cup is [kap] (low central vowel) and carp is [kaːp].

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment. Elsewhere on this blog I’ve mentioned that I’m a Canadian English speaker, and, as I said in my reply to Pewi above, I made the unjustified assumption that my readers are also North American English speakers. This was definitely sloppy on my part, and I’m glad that people are bringing up these issues in the comments.

LikeLike

I don’t really agree with the assessment here. The voicing of following consonants has an effect on length, but different phonemes have intrinsic lengths associated with them. Compare south-of-England “cot-caught” (albeit with a qualitative difference too) or “bed-bared”, or north-of-England “bad-bard”, or Antipodean “cup-carp” as JC mentions.

In North America the LOT-PALM merger and /æ/-tensing have introduced more variability, but /ɪ, ɛ, ʌ, ʊ/ still tend to be intrinsically short here just as they are in Britain. It’s why non-native [i] frequently gets misheard as /ɪ/.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are correct that different sounds have different intrinsic lengths, but I don’t know how this bears on the phonological rule related to vowel lengthening. Both can be true at the same time. It’s possible for for /ɪ/ and /i/ to be lengthened before voiced sounds, and also for [ɪ] to be shorter than [i] in all contexts.

I also don’t agree that length is the main reason for non-native confusion between [i] and [ɪ]. Many languages lack a distinction between /ɪ/ and /i/ in the first place, including major world languages like French, Spanish, Mandarin and Russian. Learners coming from such backgrounds will have more difficulty learning this vowel pair because the vowels are phonetically similar and because they have no previous experience distinguishing them in running speech.

LikeLike

Well, I wasn’t speaking of non-native confusion but rather native confusion: an NNS’s “sheep” or “beach”, pronounced with a fully short [i] rather than the clipped [iˑ] or [ɪi] of an NS, is liable to be misheard by the latter as “ship” or “bitch”. I’ve experienced this myself a few times and heard others remark on it too.

LikeLike

I agree with Lazar. Vowel length in English does play a role albeit always in conjuntion with quality. That is why most transcriptions indicate it for i/i: and o/o: and also a:/^ (with the added distinction of quality) – although there are also those that transcribe the quality alone.

Linguistically I can see either choice as valid but pedagogically, it is invaluable to indicate lengths for foreign language learners. Those coming from languages that have the length distinction will find it something to relate to. Those coming from languages without the length disctinction will have something to focus on and choose minimal pairs to practice on. There’s even a book called Ship or sheep specifical for ESL/EFL speakers.

Native learners of the English spelling, on the other hand, greatly benefit from the long/short vowel distinction based on letter names. It allows them to internalize regularities such as rid/ride, bad/bade, etc. It does help that the ‘long’ vowels are actually longer than the ‘short’ even if only by virtue of being diphthongs.

So I would consider both to be very useful to teach. But I would definitely add the allophonic length variation to the education of teachers. I’ve come across experienced teachers who insist that the vowels in rite and ride are entirely different.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Vowel length in English does play a role albeit always in conjuntion with quality. That is why most transcriptions indicate it for i/i: and o/o: and also a:/^ (with the added distinction of quality) – although there are also those that transcribe the quality alone.”

The amount of detail that goes into a transcription depends on the goals of the transcriber, and that’s why you’ve seen variation. Sometimes the goal is phonetic transcription, where every detail is represented. This would include predictable details like vowel length, vowel nasalization, t-flapping, glottalization, etc. (based on dialect, of course). Sometimes the goal is phonological, in which case these predictable phonetic details are omitted. Additionally, it depends on what dialect is being transcribed (which several people have pointed out in the comments above).

“Native learners of the English spelling, on the other hand, greatly benefit from the long/short vowel distinction based on letter names. It allows them to internalize regularities such as rid/ride, bad/bade, etc. It does help that the ‘long’ vowels are actually longer than the ‘short’ even if only by virtue of being diphthongs.”

I disagree that students benefit from the orthography-based classification, and I gave numerous reason in my post for why I disagree. The traditional system based on orthography does not correctly distinguish between all the vowels of English. A system based on the phonetics and phonology of English can distinguish them all. How is there even a choice here? Why would you choose to teach an obviously inefficient system?

“I’ve come across experienced teachers who insist that the vowels in rite and ride are entirely different.”

Where where these teachers from? There’s a phenomenon known as “Canadian Raising” which is active in most Canadian dialects, and now also many dialects of the northern United States. You can google that term for more details, but in a nutshell Canadian Raising refers to a process where certain diphthongs raise from low to mid vowels before voiceless obstruents. The words you gave here are classic examples of where Canadian Raising applies. For speakers of these dialects (like me!), the phonetic vowels in “rite” and “ride” are different, even though they correspond to the same underlying phoneme.

LikeLike

Re 1: We’re talking about 2 different things. Yes, the level of detail of transcription differs depending on the purpose. But these were decisions made for the same purpose: dictionary making. There are 3 options: indicate quality only, quantity only, quality and quantity. All 3 have been used at some point (I don’t have the rerference to hand). With the third being the currently accepted practice. In fact, the final /i/ in things like -ity or -ly. Is often transcribed as /i/ (without length but with the quality of SHEEP) to indicate a variation in pronunciation among native speakers: http://phonetic-blog.blogspot.de/2012/06/happy-again.html

Re 2: I was talking about usefulness for the learning of orthography. While the allophonic length variation or the quality distinction have no practical use I can see for a student (apart from knowledge of the phonological system for its own sake), the traditional long/short distinction based on letter names (and reflecting some historical trends), is directly useful for teaching orthography to native speakers (not much use for EFL/ESL). These students do not need to distinguish between vowels of English – they already know how to do that, they need a reliable guide to the precious few regularities of English orthography. Struggling spellers do not grapple with lack/father but rather lack/lake.

You say: “A phonetics-based approach teaches students about how pronuncation actually works, and it’s a model that you can use for literally any language on Earth.” But nobody teaching short/long distinction is doing it to teach ‘how language actually works’, it’s just a means to an end. They barely distinguish between vowel letters and vowel sounds, let alone get into the level of abstraction that can be applied to ‘any language’. You may insist that ‘how language works’ is what they should be teaching, but that’s a different argument. They just try to give their students the minimal metalanguage to be able to navigate orthography. Another thing they do, which would drive you crazy is that they syllabify words like ‘kitten’ as ‘kit-ten’. But again, it works for that particular purpose.

Re 3: These were both mid-West Americans but they were not basing this on dialectal phonological difference. They did not understand phonemes and allophonic variation. They simply felt that the /ai/ in ride and write sound sufficiently different as to not being the same sound. Of course, for non-native speakers who struggle with final devoicing but have no trouble with length, the length is not a bad proxy for learning to distinguish between the 2.

LikeLike

Here’s the reference to Re 1 from previous comment: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/ipa-english-uni.htm. See section 5.

LikeLike

The original poster (let’s call him LG) made several points that may be condensed as follows: The so-called SHORT/LONG “distinction has nothing to do with length” (although there are “vowels with different physical durations” which don’t figure into the traditional short/long paradigm)–rather, this approach is based on “totally arbitrary labels that students simply memorize,” and these labels (as used in the traditional model) should be jettisoned because “[t]here is a real system to the way that vowels work in English.” With respect to your replies, I have resources to address only a few:

“[I]t is invaluable to indicate lengths for foreign language learners”–evidently, our experience differs. this element has literally never entered into any of my (nearly 20-year) teaching career in English L2 settings, whether domestic (in a GA/NAE-speaking region of the U.S.) or international (several years total between Japan & Russia), across the gamut of student populations; not only would I have to clarify that “vowel length” must not be confused with the vowels-as-letters ‘traditional’ approach, but vowel “length” as a concept differs substantially from language to language. My students consistently struggle–and request assistance–with differentiating between core phonemes, not “length” as such. As far as your contention that “[t]hose coming from languages without the length disctinction will have something to focus on and choose minimal pairs to practice on,” neither I nor any colleagues have, to my recall, ever used minimal pairs for such a purpose; pairs/trios are very helpful for distinguishing phonemic differences (and some allophones, esp. for more advanced students), but none of my pupils has ever even broached the topic of vowel length as “something to focus on”; the most I can recall is a very general question or two over the years about whether, for example, the vowel sound in “tune” is ‘held’ as long as that in “troop”

“Native learners of the English spelling, on the other hand, greatly benefit from the long/short vowel distinction based on letter names”–I would be thrilled to meet the “learners” in question; I myself (and the 5 children I’m currently helping my wife homeschool) have become resigned to languishing through materials based on the vowels-as-letters approach, and teach/learn in spite (rather than because) of the flaws in this ‘system’ (primarily, the innumerable exceptions which render the entire paradigm questionable at best)

“It allows them to internalize regularities such as rid/ride, bad/bade, etc.”–even these alleged “regularities” are not ‘regular’: forbade, for example, follows the same pronunciation as “bad” (rather than “bade), and I submit that few linguists would predict a distinct pronunciation for “gon” as compared to “gone.”. In fact, so-called ‘silent’ -e has unpredictable effects that compromise the faux “long vowel” rule: “live” can be pronounced 2 distinct ways; “I’ve” is not “give” minus the initial g-consonant; “love” does not sound like “stove”; with terminal -e added, “on” sounds like “won” (rather than “own”); and all of these pairs are (at least in ‘newscaster’ general American) homphones: ho (Santa’s greeting)-hoe (garden tool); Flo (woman’s name)-floe (ice)-flow; toe-tow; do (musical note)-doe (deer)…we could go on. The only utility I can find in the long/short vowels-as-letters model is that constructions (e.g. -ay for diphthong /ei/) which produce less variance than others (e.g. -ea for the vowel sound in “bread”) might be presented as patterns for some pronunciations. Yet the inescapable and ubiquitous reality of exceptions re: the general approach renders this long/short ‘system’ a dubious pedagogical prospect

LikeLike

Short version:

In RP and related accents, quantity and quality are locked together, and British phonologists tend to notate both.

In Scottish English (and Scots) and North American English, only quality is phonemic: quantity can be predicted by a vowel length rule (not quite the same rule in all varieties). U.S. phonologists typically only mark quality when they use the IPA, though the old Kenyon-Knott notation marked tense quality using homorganic diphthongs (/i/ is KIT, /iy/ is FLEECE, e.g.)

In Southern Hemisphere English and Caribbean English, quality is phonemic separately from quantity. There isn’t an independent notational tradition, and for historical reasons UK-style notation is generally used.

LikeLike

I can see how the AmE v BrE would make a difference here. Compare these 2 instructional videos: BrE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xs92TR3ShJc v. AmE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuK3A3pBQlc. It’s clear that the length is less of a distinction in AmE. But for a learner, it seems to me that length could still be a useful guide even in AmE when the quantity distinction is less. Although the AmE instructor focuses only on purely articulatory differences, one possible benefit would be that the same principle could be applied when exposed to other varieties.

LikeLike

I’ve heard a lot of people claim this kind of fundamental cleft between RP and NAmEng, but I don’t see it. Neither RP nor GA has any pure length oppositions, and in both varieties the high free vowels tend to be (at least narrow) diphthongs in contrast to their intrinsically short checked counterparts. For me (I’m natively rhotic, and speak something akin to GA), “bade” and “bead” are definitely longer than “bed” and “bid” (ditto “bait/beat” and “bet/bit”), and very much unlike the short monophthongal realizations that you’d hear in Scottish English. And for me, too, the vowel in “father” is longer than one in “feather” – the former being a free phoneme and the latter a checked one. Beyond the quirk of having lost the checked LOT phoneme and merged it variably into THOUGHT or PALM, I don’t think there’s a fundamental, generalizable difference between the two national varieties in terms of vowel length.

LikeLike

You wrote: “If you pronounce an English vowel that’s normally long as short instead, it won’t change the meaning of the word. ”

What about the words sheet and shit?

LikeLike

The differences between the vowel of “sheet” a’d the vowel of “shit” are more than just length. Changing the length of either vowel — producing “sheeeeeeeeet” or “shiiiiiiiiiiiiii,” for instance — wouldn’t change that vowel into the other one.

LikeLike

I 100% agree that the usual method of teaching about “long” and “short” vowels in English language education is far more trouble than it is worth. As is mentioned in other comments, yes the situation is nuanced and yes vowel length is a real linguistic phenomenon that matters more in some languages/dialects than in others (even various English ones). However, if the question is about how the vowels in a printed English word should be read, then the standard rules about “long” and “short” vowels are absurdly confusing and full of exceptions.

LikeLike

Follow the link above and you will see my daughter Jordan speaking backwards. She’s been doing it since she was a little girl.

Diane. dr10453.gmail.com

LikeLike

.

LikeLike